Let me ask you a question:

みなさんにひとつ質問があります。

Now, let’s look at some data related to that question. The following is from the EF English Proficiency Index (EF EPI), an international ranking. In 2023, Japan ranked 87th out of 113 countries. That places Japan in the “low proficiency” group. What’s more, Japan’s ranking hasn’t improved for over ten years. Nearby countries like South Korea, China, and Vietnam are steadily overtaking us (Nippon.com, 2023).

この質問に関連して、ひとつデータをご紹介します。これは、EF という国際的な調査機関が発表している「英語能力指数(EF EPI)」のデータです。2023年、日本は113か国中87位でした。つまり、「英語力が低いグループ」に分類されているということになります。さらに、この順位はここ10年以上、ほとんど変わっていません。韓国や中国、ベトナムなど、アジアの国々にも追い越されているのが現状です(出典:Nippon.com[2023年])。

Next, let’s turn to the TOEFL test, a global English assessment widely used by students applying to overseas universities. According to 2023 data, Japan’s average score was 73. The global average, however, was about 86.6. This shows that Japan’s performance is quite low. China (87) and South Korea (86) both scored higher than Japan (Educational Testing Service, 2023).

次に、TOEFLテストについても見てみましょう。このテストは、海外の大学への進学を目指す人など、世界中の人々が受験しているものですが、2023年のデータによると、日本の平均スコアは73点でした。一方、世界全体の平均はおよそ86.6点で、日本のスコアはかなり低い水準にあることがわかります。また、日本よりも中国(87点)や韓国(86点)のほうが平均スコアは高くなっています(出典:Educational Testing Service[2023年])。

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) also conducted a survey in 2022 on the English ability of Japanese high school seniors. Only 8.8% had reached the B1 level, which is defined as the ability to express one’s own ideas in English to some degree. The government had set a goal for over 50% of students to reach B1, but that target has not yet been met (MEXT, 2023).

次に、文部科学省が実施した調査によると、これは2022年に行われたもので、高校3年生の英語力に関するデータですが、その中で、「自分の考えをある程度英語で話せるレベル(=B1レベル)」に達していた生徒は、わずか8.8%でした。実は、政府は「高校生の50%以上がB1レベルに到達する」という目標を掲げていましたが、その達成にはまだ至っていないのが現状です(出典:MEXT[2023年])。

These realities made me feel strongly that we need to change English education. That’s why I decided to start researching the problem myself. But research is like a journey—you don’t reach the goal right away. So I explored the gap between academic ability and speaking ability from various angles. And I came to a key realisation.

こうした現実を知ったとき、私は心の底から「英語教育を変えたい」と思うようになりました。そして、「それなら、自分で研究してみよう」と決意したのです。とはいえ、研究は旅のようなもので、いきなりゴールにたどり着けるわけではありません。そこで私は、さまざまな角度から「学ぶ力」と「話す力」のギャップについて研究を重ねました。その過程で、私はある大切なことに気がついたのです。

Many students in Japan have strong academic skills in reading and writing, but they struggle with everyday conversation and natural communication. Once I noticed this, I decided to focus not on academic English but on the ability to speak smoothly—on fluency and pronunciation.

私が気づいたのは、多くの学生がリーディングやライティングといった学術的なスキルには優れている一方で、日常的な会話や自然なコミュニケーションを苦手としている、という現実でした。この気づきをきっかけに、私は英語の学術的なスキルではなく、「スムーズに話す力」、すなわち流暢さと発音に特化した研究を続けてきました。

I also realised something else: many students lack both motivation and confidence when it comes to English. While English classes in Japan are gradually changing, students still don’t have enough chances to speak. And since they often just memorise vocabulary or translate texts, it’s easy to lose interest. As a result, motivation stays low. But many students continue studying without realising this connection. Even after studying English for six years, they’re left only with the feeling that they’re “bad at English.” Without understanding the reason, they start to think, “Maybe I’m just not cut out for English.” These overlapping factors help explain why it’s so hard for students to improve.

さらに、もうひとつ気がついたことがあります。それは、多くの学生が英語に対するやる気や自信をあまり持てていない、ということです。日本の英語教育は大きく変わりつつありますが、それでもなお、英語を話す機会は限られており、単語の暗記や英文の和訳といった「勉強中心」の授業が依然として主流です。その結果、英語に対するモチベーションや自信が育ちにくい状況が続いているのではないかと感じました。

ところが、多くの学生はそのような背景に気づかないまま学習を続けており、気がつけば「6年間も英語を勉強したのに、英語が苦手だ」という思いだけが残ってしまっているように見えます。さらに、理由がはっきりしないまま、「自分には英語が向いていないのかもしれない…」と感じてしまう学生も少なくありません。

私がリサーチを進める中でこうした背景に気づいたことにより、学生たちが英語力をなかなか伸ばせない根本的な理由が、よりはっきりと見えてきました。

So here’s the question:

そこで 出てくるのは、やはり、この問いです。

My answer, based on my research, is to change the educational approach. If we shift the focus to speaking and interaction, we can address a range of problems at once—fluency, pronunciation, confidence, motivation, grammar, and vocabulary.

この質問への私の答えは、研究を通してたどり着いた、「教育のアプローチを変える」という考え方でした。具体的には、「英語を話すこと・やり取りすること」を中心に据えた学びへと切り替えることで、流暢さ、発音、自信、やる気、さらには文法や語彙といった、英語の会話力に関わるさまざまな課題を総合的に改善できるのではないかと考えたのです。

But here, the next question emerges:

しかしここで、次の疑問が浮かびます。

Shifting the focus slightly, as a university instructor, I see many teachers using textbooks to structure their lessons around communication. Textbooks have strengths: they’re convenient, easy to manage, syllabus-friendly, adaptable to student needs, and culturally appropriate. However, do any textbook tasks actually help students change their attitudes toward English in a positive way? Are they designed to let students formulate and express their own ideas naturally in English?

話は少し変わりますが、大学教員としての立場から見ると、多くの教員の方々がコミュニケーションを重視した授業を行うために、教科書を活用している様子が見受けられます。たしかに教科書には良い面もあります。たとえば、授業の進行を管理しやすいこと、利便性が高いこと、シラバスの設計がしやすいこと、学生の関心やニーズに合わせやすいこと、さらに日本の文化的特性にも配慮できることなどが挙げられるでしょう。

けれども、教科書に掲載されている課題の中に、果たして学生の英語学習に対する姿勢を前向きに変えるようなものが、どれほどあるのでしょうか。

そして、教科書は本当に、学生が自分の考えを整理し、それを自然な英語で表現できるように作られているのでしょうか?

Although we try to move away from teacher-centred instruction in university classrooms, we often fall back on textbook-centred instruction instead.

大学で教える私たち教員自身も、教員中心の授業から脱却しようと努力を重ねています。しかし実際には、授業が教科書中心になりすぎてしまっているのではないか――そんなジレンマを感じることも少なくありません。

Relying too heavily on textbooks, I believe, makes it difficult for students to develop the ability to speak naturally in their own words. In other words, once the textbook is closed, students can no longer communicate in English. And so, by focusing too much on textbooks, we end up discouraging motivation and confidence and neglecting the interconnected elements necessary for language development. English should be more flexible and practical. That’s why I began advocating for student-centred classes focused on speaking and interaction.

私は、教科書に頼りすぎることで、学生が自分の言葉で自然に話す力が育たないという問題が生じると考えています。つまり、教科書を閉じた途端に、学生たちは自分の考えを英語で話すことができなくなってしまうのです。

その結果、教科書に沿って講義を進めることは、学生の英語に対する自信ややる気を奪ってしまい、英語の習得に必要なさまざまな要素――流暢さ、発音、語彙、構文、そして自発性といったものが、うまく育たなくなってしまいます。

英語はもっと自由で、実用的であるべきです。だからこそ、「英語を話すこと・やり取りすること」を中心とした、そして学生自身が主役となるような授業を進めていくべきなのではないか。私はそう考えるようになりました。

It’s just like learning to drive. You won’t become a good driver just by memorising how an engine works. Of course, the knowledge is useful—but nothing beats holding the wheel and trying it out. I believe the same is true for language learning. If we want to change how students relate to English, we need to move beyond textbooks and give them space to actually use the language in conversation. It’s not just about inputting knowledge—it’s about trying to express that knowledge in their own words.

それは、車の運転と同じです。 車の運転は、「エンジンの仕組み」を教科書でくわしく学べばできるようになるのでしょうか?もちろん、教科書で得る知識も大切ですが、実際にハンドルを握り、車を動かしてみる経験こそが何より重要です。私は、英語という言語もまったく同じだと考えています。 英語に対する学生たちの姿勢を変えるためには、教科書に頼りすぎず、自分の力で英語を使い、会話しようとする経験が必要なのです。 つまり、知識をインプットするだけでなく、「自分の言葉で英語を使ってみる場所」を授業の中に設けることが、何よりも大切だということです。

Let me shift topics briefly.

ここで、少し話がそれますが、

Speaking English can be a very complex task. It’s not just about using correct grammar—you also have to manage speed, intonation, and accuracy all at once. So improving English requires attention not only to correctness, but also to the quality of delivery. That’s where TPP comes in. TPP is a new approach and framework I developed that helps students practise fluency, pronunciation, and confidence all at once through interactive speaking tasks.

「英語を話す」という行為は、実はとても複雑な作業です。

単に文法が合っていればよいというわけではなく、話すスピード、イントネーション(声の上げ下げ)、正確さといった複数の要素を同時に意識しながら話す必要があります。

つまり、英語を上達させるには、「正確さ」「スピード」「イントネーション」といった“話し方の質”にも目を向ける必要があるのです。

そこで私が開発したのが、TPP(タイムド・ペア・プラクティス)という新しいアプローチであり、理論でもあります。

TPP is student-centred, and that’s key. It supports the development of speaking skills, while also fostering motivation and engagement—two essential elements of language acquisition. By using TPP in class, students can build their ability to speak English in their own words.

このTPPは、「学生中心のアプローチ」であるという点が、非常に重要なポイントです。

その特性ゆえに、学生のスピーキング力を高めるだけでなく、言語習得に欠かせない「やる気」や「主体的な関与」といった姿勢も同時に育てていくことができます。

だからこそ、授業にTPPを取り入れることで、学生たちは自分の言葉で英語を話す力を、実感を伴って身につけることができるのです。

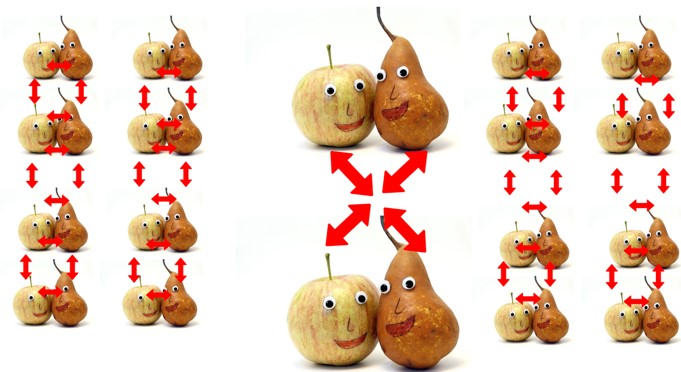

So how does it work? The method is very simple. First, students choose a topic they care about—such as their high school or university club—and write 10 to 20 questions related to that topic. What’s important here is that students use topics they’re personally interested in, not generic textbook prompts.

では、このTPPを具体的にどのように行うのか、ご説明しましょう。やり方はとてもシンプルです。

まず、学生たちにクラスで話す内容、たとえば「高校や大学の部活動」などを自由に選んでもらいます。次に、そのトピックに関して、10〜20個の質問を自分たちで考えてもらいます。

ここで重要なのは、教科書に載っているような一般的なトピックではなく、学生自身が本当に興味を持っているテーマを扱うことです。自分ごととしてとらえられる内容だからこそ、話す意欲や主体性が引き出されるのです。

Next, they form pairs and practise speaking using their own questions. Importantly, they don’t read from their notes—they speak freely. Then they switch partners and repeat. Through this repetition, they gradually learn how to sustain conversations for longer. And the most important thing is not to avoid mistakes, but to try speaking. After enough pair practice in class, I select two students at random, set a timer, and have them perform their conversations as a test. The timer helps them monitor how long they can keep the conversation going.

次に、学生たちにペアを組んでもらい、自分で作った質問を会話に取り入れながら、メモを見ずに会話をする練習をしてもらいます。そして、ペアを変えて何度も繰り返し練習することで、学生たちは会話を長く続けるための工夫や方法を自然に身につけていきます。

ここで大切なのは、「間違えないこと」ではなく、「とにかく話してみること」です。英語を話す力は、実際に声に出して試してみる中でこそ伸びていくのです。

十分な練習を重ねたあとは、ランダムに2人の学生を選び、タイマーをセットして、これまで練習してきた内容をテストします。このとき、制限時間を設けることで、学生は「自分がどれくらいの時間、英語で話すことができたか」を客観的に確認することができるのです。

As the instructor, I can also pause the interaction whenever a student stalls, makes repeated grammar errors, or misunderstands something. This allows me to provide timely support. Through this process, students start to feel real progress. They begin to believe in themselves and their abilities. In other words, they start developing a positive mindset. This is the core of Timed-Pair Practice. It’s not about memorising a textbook. It’s a training method where students talk a lot, laugh a lot, and improve their English while having fun.

学生の会話が止まってしまったとき、文法のミスが見られたとき、あるいは内容の理解が不十分なときには、教員がその場で会話を止めて指導することができます。このように、リアルタイムでサポートできることも、TPPの大きな特長のひとつです。

そして学生たちは、楽しく前向きな学習経験を通して、「自分は英語を通じて成長できる」という実感を少しずつ持つようになります。すなわち、自己肯定感や前向きな姿勢が自然と身についていくのです。

これこそが、TPPという新しいアプローチの根底にある理論です。教科書に頼るのではなく、学生たちが自分たちの言葉でたくさん話し、たくさん笑い、楽しみながら英語力を総合的に引き上げていく。それがTPPのめざす学びの姿なのです。

And TPP produces positive chain reactions. As I mentioned earlier, students build confidence through this approach because it puts them at the centre of the learning experience. Instead of passively being taught, they actively take control. As a result, their motivation improves, they become more engaged, and they develop metacognitive skills—the ability to reflect on how they’re learning.

そして、このTPPによって得られた成果には、良い連鎖反応が生まれています。

最初にTPPの理論をご紹介したときにも触れましたが、学生の「自信」が高まることは、その大きな特長のひとつです。これは、TPPが学生中心で行うアプローチだからこそ実現する効果です。

つまり、先生に教えてもらうだけでなく、自分から積極的に学ぼうとする姿勢が育つことで、やる気が引き出され、英語に対して前向きな気持ちで取り組めるようになります。さらに、「自分がどのように学んでいるか」を振り返る力、いわゆる「メタ認知力」も、少しずつ養われていきます。

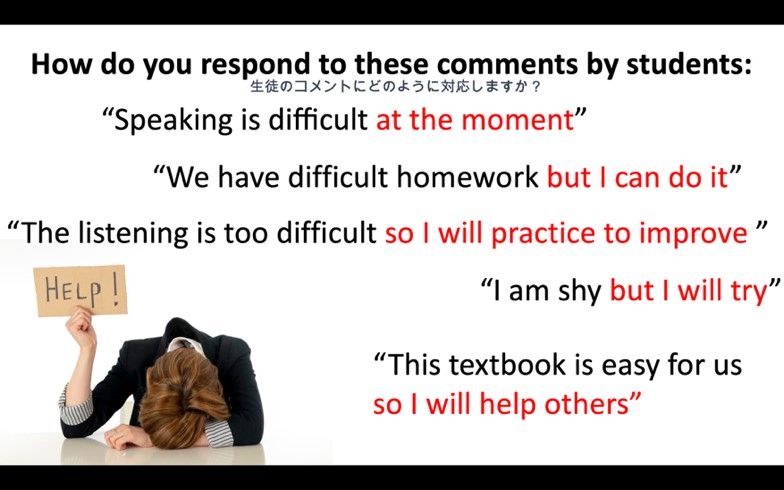

For example, they start thinking: “Speaking is hard now, but I’ll get better.” “This homework is tough, but I can do it!” “Listening is difficult, but I’ll give it a try.” “I’m shy, but I’ll do my best.” “This is easy for me, so maybe I can help someone else.” As students experience these positive moments, they gradually become aware of their own strengths and take steps to grow. In other words, they develop a positive attitude toward learning English.

たとえば、こんなふうに考えられるようになるのです。

「話すのは今は難しいけれど、これからはできるようになる」

「難しい宿題があるけれど、私にはきっとできる!」

「リスニングは難しすぎるけど、とりあえず練習してみよう!」

「私はシャイだけど、思い切ってがんばってみよう!」

「このテキストは私には簡単だから、他の人を手伝ってあげよう!」

このように、学生たちは少しずつポジティブな考え方を持てるようになっていきます。

つまり、TPPを使った授業を通して、こうした前向きな学習体験を重ねることで、学生たちは自分の力に気づき、自分自身を高めようとする姿勢を育んでいけるのです。

そして何よりも、英語に対して前向きに取り組む姿勢が、自然と身についていくようになります。

By incorporating TPP into the classroom, we nurture that positive mindset, which helps students become more aware of grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and content. And ultimately, it leads to greater fluency.

このように、TPPを通じて前向きな学習姿勢が育つことで、学生たちは次第に、話の内容や文法・語彙・発音の重要性にも自ら気づけるようになっていきます。

そしてその積み重ねが、最終的には英語の流暢さ(スムーズさ)の向上へとつながっていく、そんな好循環が生まれるのです。

References

Educational Testing Service, 2023. TOEFL iBT® Test and Score Data Summary 2023. Princeton, NJ: ETS. Retrieved from: https://www.ets.org/pdfs/toefl/toefl-ibt-test-score-data-summary-2023.pdf.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology–Japan. 2023. 令和4年度「英語教育実施状況調査」概要 [Overview of the FY 2022 English Education Implementation Survey] Tokyo: MEXT.Retrieved from:https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20230516-mxt_kyoiku01-00029835_4.pdf.Nippon.com, 2023. Japan’s English Proficiency Continues to Drop Among Non–English-Speaking. Japan Data. Retrieved from Nippon.com website: Nippon.com/en/japan-data/h01843/