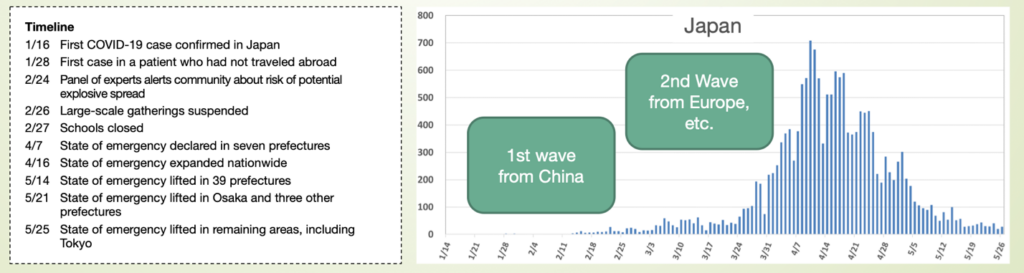

Trying to speak English is challenging without encouragement. This sentiment is often expressed by high school students in Japan during their English classes. However, I observed a similar issue while working at the University of Edinburgh. I was teaching academic English primarily to international students from Asia who were preparing to enter their academic programs. While they excelled at writing their reports and researching their chosen field of expertise, they still struggled to make friends from outside their country. It had nothing to do with their English proficiency but simply as a result of their skills to talk to others – especially native English speakers. These students lacked the appropriate encouragement and were not equipped with effective communication strategies to engage with British students. As a result, even after obtaining their degrees, they had not fully benefited from their experience of living in the UK. There were areas that needed attention – namely their fluency and pronunciation as this would improve their interaction with UK students. I wanted to assist them but didn’t know how, and I lacked the time to provide adequate support. However, everything changed with the onset of COVID-19.

While we all recall the challenges of dealing with this potentially deadly virus,, we also remember the amount of spare time we had because of having to stay at home. We were advised to remain indoors to prevent the spread of the disease. Many of us, myself included, probably watched too much TV, consumed too much junk food, and spent excessive hours on the PS4. Well, I did anyway. Although it was fun at first, it soon became quite dull. I needed outside contact. My only outlet to the outside world was teaching my students online. Teaching university students through online platforms like Teams or Zoom presented its own challenges. However, I found that I could spend less time on administrative tasks such as organizing the classroom, distributing materials, and forming student groups, and more time actively listening to individual conversations. I observed a genuine desire among students to communicate with each other. However, they lacked opportunities to practice speaking English, which resulted in a slower pace when expressing their thoughts. And so I asked them what they actually wanted to do in our classes. These students also had not received the right kind of encouragement and I had the time to listen and help.

Their response was generally the same: to talk about topics that interested them. They were tired of studying for the entrance examinations. Focusing on reading articles or memorizing vocabulary or grammar patterns did not seem to encourage them to converse in English. They were also disappointed in their English ability, especially speaking, despite their efforts and the years spent in English classes at high school. They simply wanted to express their thoughts and ideas.

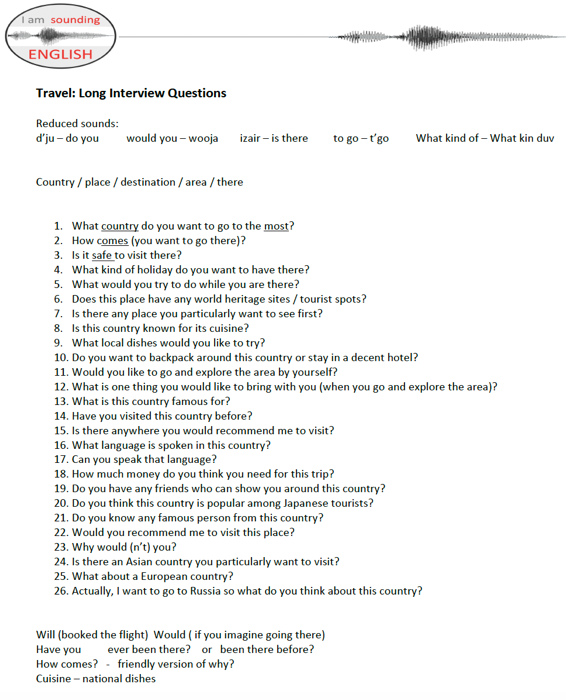

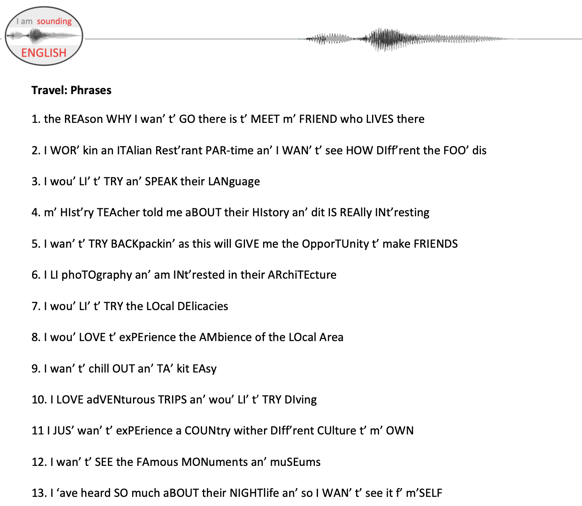

I created worksheets to help them discuss topics they enjoyed, such as food, travel, music, fashion, and even more complex subjects like the environment and post-graduation plans. Although these activities were helpful, some students found them too simplistic. However, when I asked the same questions, the response was quite different. They could not follow what I was trying to say. At such experience, it became obvious to address these gaps in comprehension but how? Students have been forced to improve their level of grammar or build their vocabulary but this did not prepare them for conversation with natives. I realized that their English courses needed to incorporate activities focused on improving pronunciation and fluency, which would help address confusion over native-speaker accents during listening and speaking exercises. However, teaching pronunciation to Japanese learners of English at university might seem the last area of second language acquisition to concentrate on in the classroom.

I first started by making videos in which I asked students a list of questions on a topic they chose. This was useful because it would push students to respond quickly to give suitable answers. The students could practice listening to me and responding to my questions, and they could practice copying my pronunciation. As I made more of these materials, I discovered improvement in their listening skills. However, not as much improvement in their English pronunciation. As a result, I decided to work on this aspect as well. I was determined to provide teaching materials that match my students’ needs and hopefully provide the right kind of encouragement.

I assigned homework where students were required to write a 200-word paragraph. By analyzing their work, I identified frequently used phrases and developed speaking drills based on these common expressions.Students would attempt to copy the native sounds but this was still too difficult to understand. However, both students and I were encouraged by improvement in fluency and so we wanted to sound more native-like. As a result, I concentrated in teaching the mechanics of pronunciation while they talked about the topics. My videos became popular and so I made a website (see below) to allow any student easy access to them. I then researched heavily to see if students could improve their fluency and pronunciation.

Over the course of a single term, students became more communicative, confident, fluent, and natural in their speech. It became evident that while speaking English can be challenging, the right kind of encouragement can lead to proficiency. With such experience, I know that they are better prepared to study abroad and benefit from a cultural exchange with native English speakers. I now use these materials and experience in my Communication Strategies class. The approach is well received by all students as they have the opportunity to stretch their spoken English in a setting that encourage them to nor equipped with suitable communication strategies to converse with other British students.

References

Omi, S., & Oshitani, H. 2020. Japan’s COVID-19 Response. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved from: https://www.mofa. go.jp/files/100061341.pdf Pipe, J. 2024. I am sounding English. Retrieved from: https://iamsoundingenglish.com